Costume dramas: Why fashion on film is having a moment?

Fashion & Film

Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film Phantom Thread takes

place primarily in a fine London Fitzrovia townhouse, the home of the talented

if temperamental fashion designer Reynolds Woodcock, played by Daniel

Day-Lewis. It’s a period piece set in the world of midcentury haute couture: we

see Woodcock woo wealthy clients, chide staff and pore over a dress’s

stitching. Yet despite the captivating elegance of it all, for some, a

meticulous fashion designer is an unexpected choice of protagonist for

Anderson, who has previously focused on porn stars, oil barons and cult leaders

in his films.

But the ins and outs of the fashion industry have been all

over our screens in recent years, both in narrative features and documentaries.

Partly this is down to the simple sumptuousness of the subject matter,

something Anderson has talked about in interviews about Phantom Thread. (“It

looks pretty!” he told the Financial Times recently.) But looking pretty is

only one aspect of it. Fashion, increasingly, is a home for drama, too.

“Looking at it historically, a fascination with the fashion

world has been there throughout almost the entire history of cinema,” explains

Marketa Uhlirova, curator of the Fashion in Film festival, which began in

London in 2006. “In the popular imagination, fashion possesses that delicious

mix of aspirational allure and vice, and this makes it an ideal setting for all

sorts of plots.” As well as narrative dramas, there have been recent

documentaries such as Dior and I, about the arrival of the designer Raf Simons

at the storied house of Christian Dior, or The First Monday in May, about the

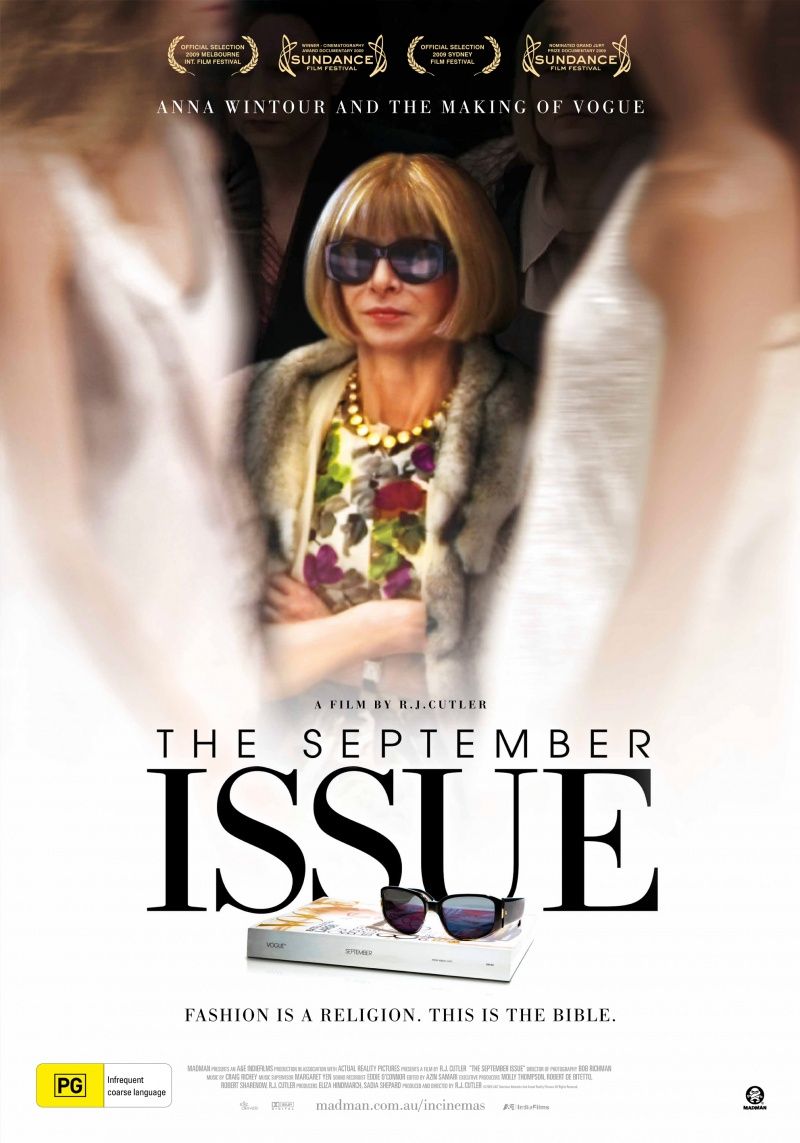

2015 Met Gala, a highlight of the fashion calendar. These are in the mould of

The September Issue and its fictionalised predecessor The Devil Wears Prada –

insidery, access-most-areas affairs, heavy on personality and intrigue,

intended to make the viewer come away feeling as if they have learned something

extra about the proceedings behind the scenes.

Fashion’s mechanics are more visible than ever now, thanks to the oversharing of Instagram accounts from the industry’s main players, so it makes sense that this genre would flourish. Yet designers must necessarily still conduct their business in private. Like secret agents, they need to hide their work from rivals if it is to be successful. Even now, when a cinemagoer might know more about the fashion industry than ever before, what goes on behind closed doors is still a mysterious business.

And streamable sleeper hits such as the aforementioned Vogue

film The September Issue, or Signé Chanel, the amazingly candid five-part BBC

miniseries about couture screened in 2006, have created a market for more. Now

any designer of note is fair game for the camera crew, whether that’s tame

interviewee Dries Van Noten in 2017 documentary Dries or avant-garde Martin

Margiela, who left his eponymous house for life as a recluse in the 2000s.

(Forthcoming documentary We Margiela focuses on the collective who run the

label in his absence.) In 2015, Apple launched M2M, a digital channel for

fashion programming, which hosts Signé Chanel and The September Issue in

between archive catwalk shows, new long-form documentaries and glossy examples

of fashion film, the genre that lies somewhere between perfume ad and magazine

spread.

It’s all a world away from Phantom Thread, whose exacting Reynolds Woodcock might be closer to romanticised depictions of designers in biographical dramas such as Saint Laurent (2014) or Coco Avant Chanel (2009). But what the current breed of documentaries share with Anderson’s film is a focus on creativity at all costs – including personal relationships and a semblance of normality. “The new infatuation is not just with fashion’s glamour and seduction, but also an interest in the creative process in which things go wrong, and the struggles and the emotional rollercoasters that come with creating a collection,” says Uhlirova. “It’s the recognition that the creation of fashion is something that possesses dramatic potential and can be given a narrative arc, as we saw with the likes of Dior and I. And it’s the incredibly intense, even obsessive relationships that are evident in the process of creation that make these stories so compelling.” Work becomes life, and it results in beautiful dresses, glamorous parties with high stakes, and a space for romance, drama and all the things that cinema has long told us can make life worth living.

Of course, Anderson must realise that fashion designers,

like film directors, are controlling as a default mode: in Phantom Thread, he

oversaw even minute details of stitching and seams in the atelier. According to

Anderson, Woodcock was inspired by Charles James and Cristóbal Balenciaga, two

midcentury couturiers whose masterful attention to detail helped define our

contemporary image of the designer as demanding, obsessive and surrounded by

devotees. That’s one important element of the appeal of it all. Art consumes,

whether you’re an eccentric fashion designer or an award-winning director. It

gives people licence to be selfish – fashion designers, with their teams and

deadlines and demands, perhaps most of all. For all the glitter and glamour

that results, maybe it’s the all-consuming work itself that attracts so many to

fashion on screen.